Pjetër BUDI

Pjetër Budi (1566-1622), known in Italian as Pietro Budi, was the author of four religious works in Albanian. He was born in the village of Gur i Bardhë in the Mati region of the north-central Albanian mountains. He could not have benefited from much formal education in his native region, and trained for the priesthood at the so-called Illyrian College of Loretto (Collegium Illyricum of Our Lady of Luria), south of Ancona in Italy, where many Albanians and Dalmatians of renown were to study. At the age of twenty-one he was ordained as a Catholic priest and sent immediately to Macedonia and Kosova, then part of the ecclesiastical province of Serbia under the jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Antivari (Bar), where he served in various parishes for an initial twelve years. In 1610 he is referred to as ‘chaplain of Christianity in Skopje’ and in 1617 as chaplain of Prokuplje.

It was in Prokuplje in southern Serbia, a year earlier, that a meeting of various national rebel movements had been held to organize a major offensive against the Turks. In Kosova, Budi came into contact with Franciscan Catholics from Bosnia, connections which in later years proved fruitful for his political endeavours to mount support for Albanian resistance to the Porte. In 1599, Budi was appointed vicar general (vicario generale) of Serbia, a post he held for seventeen years. As a representative of the Catholic church in the Turkish-occupied Balkans, he lived and worked in what was no doubt a tense political atmosphere. His ecclesiastical position was in many ways only a cover for his political aspirations.

Pjetër Budi was filled with an ardent desire to see his people freed of Turkish bondage and he worked actively to this end. He is known in this period to have had contacts with figures of influence such as Francesco Antonio Bertucci and with Albanian rebels seeking the overthrow of Ottoman rule. But Budi was no narrow-minded nationalist. As far as can be judged, his activities, then and later, were directed towards a general uprising of all peoples of the Balkans, including his Muslim compatriots.

In 1616, Pjetër Budi travelled to Rome where he resided until 1618 to oversee the publication of his works. From March 1618 until ca. September 1619, he went on an eighteen-month pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. Back in Rome in the autumn of 1619, he endeavoured to draw the attention of the Roman curia to the plight of Albanian Christians and raise support for armed resistance. On 20 July 1621, he was made Bishop of Sapa and Sarda (Episcopus Sapatensis et Sardensis), i.e. of the Zadrima region, and returned to Albania the following year. His activities there were often more political than religious in nature. One of his interests was to ensure that foreign clergymen were replaced by native Albanians, a step which could not have made him particularly popular with some of his superiors in Italy. In December 1622, some time before Christmas, Pjetër Budi drowned while crossing the Drin river.

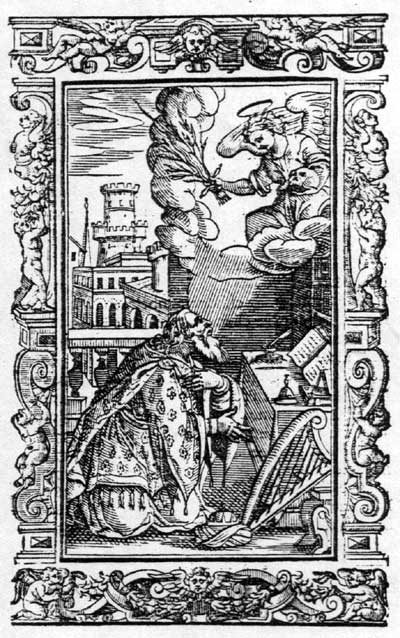

Budi’s first work is the Dottrina Christiana or Doktrina e Kërshtenë (Christian Doctrine), a translation of the catechism of Saint Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621), which was published in Rome in 1618. Of more literary interest than the catechism itself are Budi’s fifty-three pages of religious poetry in Albanian, some 3,000 lines, appended to the Christian Doctrine. It constitutes the earliest poetry in Gheg dialect. Much of it was translated from Latin or Italian, though some is original.

Among Budi’s other publications are: 1) the Rituale Romanum or Rituali Roman (Roman Ritual), a 319-page collection of Latin prayers and sacraments with comments in Albanian; 2) a short work entitled Cusc zzote mesce keto cafsce i duhete me scerbyem (Whoever says Mass must serve this thing), a 16-page explanation of mass, and; 3) the Speculum Confessionis or Pasëqyra e t’rrëfyemit (The Mirror of Confession), a 401-page translation or, better, adaptation of the Specchio di Confessione of Emerio de Bonis, described by Budi as "some spiritual discourse most useful for those who understand no other language than their Albanian mother tongue." Both the Roman Ritual and the Mirror of Confession are supplemented by verse in Albanian.

At first glance Pjetër Budi can be regarded as a translator and publisher of Latin and Italian religious texts. His significance as a prose writer, however, goes beyond this. His various prefaces, pastoral letters, additions and postscripts, amounting to over one hundred pages of original prose in Albanian, betray a good deal of style and talent. His language is authentic and refreshingly idiomatic when compared to Gjon Buzuku before him and Pjetër Bogdani half a century later. Though not as elaborate and abstract as Bogdani, who possessed a greater vocabulary, Budi remains the most spontaneous and prolific writer of the age.

Pjetër Budi is also the first writer from Albania to have devoted himself to poetry. His works include some 3,300 lines of religious verse, almost all in quatrain form with an alternate rhyme. Though Budi’s religious verse is not without style, its content, being imitations of Italian and Latin moralist verse of the period, is not excessively original. He prefers Biblical themes, eulogies and universal motifs such as the inevitability of death. What is attractive in Pjetër Budi’s verse is the authenticity of feeling and genuine human concern for the sufferings of a misguided world.

|

BACK

![]()