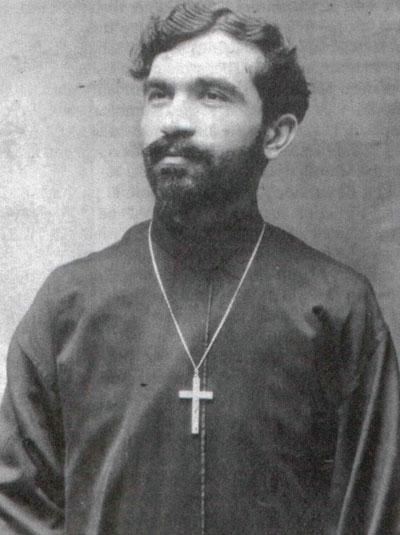

Fan NOLI

As Metropolitan of the Albanian Orthodox Church in America and former prime minister of Albania, Fan Noli was not only a noted religious figure, statesman and poet, he was also a gifted translator. His elegant Tosk Albanian versions of Shakespeare were and are much admired in the Albanian world. In this text, Noli tells us of his first encounter with ‘the bard.’

SHAKESPEARE AND I

It was in 1897, and I was fifteen years old, when I met Shakespeare for the first time. It was one of the greatest events of my life. I was studying then at a Greek gymnasium. Though an Albanian by descent, I had to go to a Greek school in Adrianople because Albanian schools were not allowed by the Turkish government.

One morning I went to the dining-room to get my microscopic breakfast consisting of a tiny cup of black coffee without sugar. It was just a few sips, and nothing else. At the long table where I was sitting I noticed four strangers, two men and two women, who were having that same breakfast. The ladies were conspicuous for their extravagant hats, whose feathers almost reached the ceiling. They were noisily discussing the problems involved in staging Hamlet, which they expected to play at the local theatre. I knew immediately that they were actors and actresses of an itinerant Greek theatrical company. From their conversation I gathered that the two young actors could read and write Greek, but the two handsome actresses were illiterate. They could not even sign their names.

After that frugal breakfast of a demi-tasse of Turkish coffee, the two boys left. Before doing so they said: ‘Now, you girls study your parts’. They replied: ‘How can we do it? We cannot read’. Then the actors said: ‘You ask that boy’ (meaning me) ‘to help you. He is studying at the gymnasium and he can read Greek’. The actresses answered: ‘We have no money. How can we pay him?’ The actors said: ‘We have no money either, but we can fix that. We can give the boy free tickets to all our performances’. Looking at me they said: ‘Would you be satisfied with that?’ I jumped at the offer without any hesitation.

The actresses handed me their parts and we started immediately. One of them was playing Ophelia and the other Hamlet’s mother, the Queen. The procedure was this: I would read the part, sentence by sentence, and the actresses would repeat them.

Soon afterwards I got my second job with the same company. The prompter fell sick and there was no one to replace him. Very few of the actors could read the catharevousa Greek (an artificial pseudo-classical dialect). The two actresses I was training suggested to the director: ‘We know a boy who could do it’. It was me again, and once more I jumped at the job without any hesitation. That gave me an opportunity to prompt Shakespeare’s Othello, and I could prompt it almost without looking at the stage version at all. I could recite all the monologues in Hamlet and Othello in Greek in a few days.

One night something happened that horrified me. Costas Tavularis, who was playing Othello, almost strangled Desdemona in order to give a realistic performance. I heard his wife, Mrs Tavularis, who was playing the unlucky Desdemona, scream for help and beg her husband: ‘Don’t press so hard! You are going to kill me!’ I gave the signal to pull down the curtain and prevented murder.

After I graduated from the gymnasium, I went to Constantinople and took the boat to Athens to look for a job. One of the first things I did in Athens was to go to the office of the Tavularis troupe and ask them to give me work in their theatrical company. They were glad to do it. They gave me a job right away, copying parts.

The way Shakespeare’s plays were presented to the Greek public in the year 1898 was rather curious. For instance, after the third act, Hamlet and Ophelia would come out on the stage without changing costume and sing some commonplace duet which happened to be popular, something like Frank Sinatra’s crooning. And what happened after the last act of Hamlet? A worthless, one-act modern comedy was played. The director of the company gave this explanation: ‘The public could not stand the terrible tragedy of Hamlet without some light music between acts and a refreshing comedy at the end’. After all, that was what the ancient Greeks used to do: a short comedy always followed a tragedy.

There was no fixed salary paid to the actors. They received a certain percentage of the profits, and the profits were not sufficient to enable the actors to make a living. The end of each season in every city was always the same. Most actors were stranded in whatever city they happened to be. They had to wait there penniless and starving until they got a new job and the price of a ticket from some theatrical manager. I was always among those stranded.

The worst of all our theatrical adventures was that of Ponto-Iraklia in Anatolia. The receipts of the first performance showed that the whole thing would be a ghastly failure. Two weeks later the company director ran away in the night with the receipts. The actors had to shift for themselves and give performances in a dingy hall to keep alive. It was in the midst of that misery that I realized the dearest dream of every actor. Both Hamlet and Ophelia were sick in bed from starvation and exhaustion. The problem was whether to postpone the performance or to go ahead with it and get a few pennies with which to buy food and keep alive as long as possible. I was asked whether or not I could take the place of the star and play Hamlet. I jumped at the offer before they could change their minds. After all, I knew the part better than any star I had ever prompted.

The trouble came when we tried to find someone to play Ophelia. There was only one person who was still on her feet. Her name was Caliroe. She was lame and had never in her life appeared before the footlights, not even in a minor role. She served as maid to her sister, who was the leading lady. Nobody imagined that the poor creature had ever entertained the ambition of playing Ophelia, The unexpected happened. When the lame girl was offered the part of Ophelia she could hardly believe her ears. She confessed that she had secretly been preparing to play Ophelia all her life.

So the tragedy of Hamlet was performed the very next evening in this improvised fashion and had an enormous success. No one in the audience suspected that Ophelia was lame. She was placed on a chair and played the part sitting. I, as Hamlet, did my best to prevent the audience from noticing that something was wrong with Ophelia. Since Hamlet is supposed to be half mad, I made all kinds of pirouettes around the chair to emphasize that point.

Ophelia was expected to follow my movements with her eyes in utter amazement. Years later, I was reminded of the lame Caliroe when I saw the aging Sarah Bernhardt give a marvellous performance with her voice, her face, and her arms, though she could hardly stand on her feet.

About two weeks later a freighter carrying bones for fertilizer was forced by a storm to take refuge in the port of Ponto-Iraklia. Its merciful captain was touched by the misery of those Shakespearean actors, some of whom had been reduced to skin and bones. He offered them free meals and free transportation for the two-day journey to Constantinople. Most of them were so weak that they had to lie down during the voyage, until the kindly sailors revived them with food. That was what was needed to cure them and put them on their feet again.

The final catastrophe came in Alexandria: stranded again; starving again. The terrified actors and actresses left for Athens one after another on the first ship they could get. I concluded that this was the end of my theatrical career. There was no sense in sticking to a profession thattook me from one end of the Mediterranean to the other with starvation threatening me in every port. So I took leave of the theatre, but not of Shakespeare.

Rescue came for me in the offer of a teaching position in Shibin-el-Kom, a few hours from Alexandria. I jumped at the chance, and took the first train for Shibin-el-Kom. Up to that date I had read Shakespeare in a worthless Greek translation. It was time for me to read him in his own language. I found an English missionary who helped me with free English lessons. I owe it to him that when I came to the United States in 1906 I could pass the language examination with the immigration officers in a few minutes.

I landed in New York and went to Buffalo, and from Buffalo to Boston. And there I met my old friend Shakespeare again in the Castle Square Theatre, presented by two excelllent performers, E. H. Sothern and his wife, Julia Marlowe. I shall always be grateful to those two great artists. Until then I had read Shakespeare in Greek and seen him on the Greek stage, but Sothern and Marlowe gave me the unforgettable experience of seeing Shakespeare on the stage in English.

My first years in America were devoted to obtaining my education. Then one day a friend of mine, the late Faik Konitza, who had a Master’s degree from Harvard, made a suggestion that we two should divide all Shakespeare’s plays between us and translate him into Albanian. He made only one reservation, that Romeo and Juliet belonged to him. I accepted at once on the condition that Hamlet should belong to me. So we both started. I began with Othello, which was published in Albanian in 1916, and ten years later my translations of Hamlet, Julius Caesar, and Macbeth were published in Belgium. As I read my Albanian versions now, I think that Macbeth was my best, because it was the last, and by that time I had really learned the tough job a little better. I am glad to say that some of our young Albanians are continuing the work of translating Shakespeare.

So far as I am concerned, I have deserted my old friend Shakespeare for the last thirty-eight years, owing to several pressures, one of which was the Second World War. I hope to go back to him and make good by giving some more of his masterpieces to the Albanians. I can do it. I am still young. I am only eight-two years old.

[Shakespeare and I, published in The Listener, 15 October 1964.]

|

BACK

![]()